Recent debates have erupted online over the reasoning of Senior Advocate of Nigeria, Femi Falana (SAN), regarding the trial of officers accused of plotting a coup against the government of President Bola Tinubu. Critics have questioned his assertion that such alleged offenders cannot be tried by a court martial under Nigeria’s constitutional democracy, citing the Armed Forces Act, which criminalizes mutiny and failure to suppress mutiny.

While these critics ask for legal authority, a deeper question emerges: Can a court martial, convened by the President—who is also the alleged target of the mutiny—be expected to act independently and fairly?

Courts Martial and Impartiality

Courts martial are constituted under the authority of the military hierarchy, ultimately reporting to the Commander-in-Chief, who is the President. If the alleged offence is a direct attempt against the President, the very office that convenes the tribunal is simultaneously the victim. Expecting impartiality in such circumstances is unrealistic.

The principle of justice demands that adjudicators be independent of the parties involved. When the President is both the alleged victim and the authority that appoints the judges, the independence of a court martial is inherently compromised.

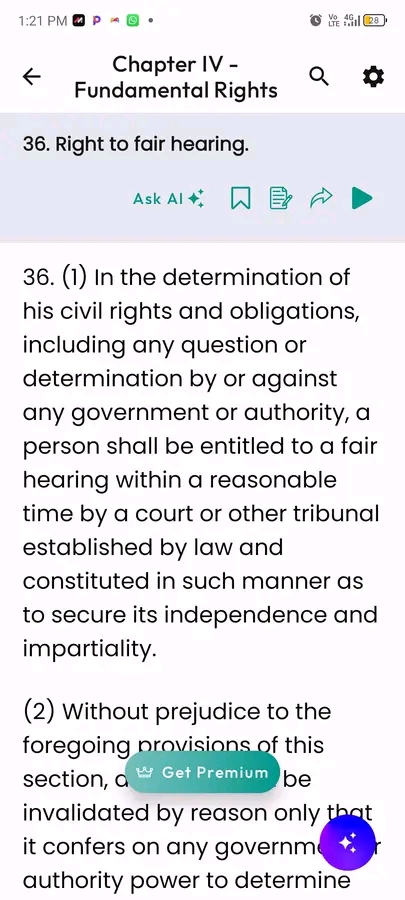

The Constitution is Supreme

Nigeria’s Constitution is the supreme law of the land. No statute, including the Armed Forces Act, can override the constitutional guarantees of a fair hearing (Section 36 of the 1999 Constitution) or the broader principles of due process. Falana’s argument rests on this premise: an alleged coup is not merely a military issue; it is a national matter that concerns every Nigerian.

Beyond Military Discipline

Attempting a coup or plotting to overthrow the government transcends ordinary military discipline. It involves national security, the stability of democratic governance, and the rule of law. Treating such offences as purely military risks undermining public confidence in the justice system.

Civilian courts, in contrast, provide:

Impartial adjudication free from the influence of the alleged victim,

Transparency and procedural safeguards, and

Public confidence that justice has been done.

Conclusion

While the Armed Forces Act empowers courts martial to try service members for mutiny, when the alleged offence directly targets the President, the Constitution must prevail. The independence, impartiality, and credibility of civilian courts make them the proper venue for trying alleged coup plotters. This is not just a legal argument—it is a matter of national interest and public trust.

In matters where the life of the Commander-in-Chief and the stability of the nation are at stake, justice must not only be done; it must be seen to be done. And for that, civil courts, not military tribunals, are the only credible option.

Published by Chuks Nwachuku